show recap: dead & company at the sphere

The people in front of me in the Sphere security line fucked up. Dead & Co had already started playing, you could hear tinkling guitars piped all through the interior of the venue. We were the last stragglers in the TSA-esque experience that precedes all large format concerts now, and I watched as a Sphere employee pulled a fresh pack of edibles from the purse of the woman ahead of me: a cartoon-printed plastic bag of gummies, its provenance likely one of the many dispensaries that have popped up around Vegas since recreational legalization.

Their crew was mixed-gender, looked to be in their fifties, wore groovy but functional clothing. Maybe they had followed the Dead in the '90s and weren't aware of the austerity of modern concert security culture. Their weed was now headed for the trash can. Should have decanted those gummies at the very least, I thought, a little smugly. Out of the package they just look like snacks. Fools! My own legally purchased gummy was dissolving in my stomach, naturally.

The crew took it on the chin, to their credit. One of the men actually said something like, "Aw, shucks!" They were oriented to time and space enough to avoid quibbling with the policies of the Sphere. And they probably knew something I didn't know yet, which is that the culture of friendship of the Dead would almost certainly provide them with whatever they required inside...

Up top: I am not a huge fan of the Grateful Dead. I have not listened to much of their recorded music and have never been to one of their offshoots' shows. I heard the Sublime version of "Scarlet Begonias" before I heard the original (sorry—hazards of growing up in Vermont in the 1990s). Between pilfering my father's Rolling Stone issues as a kid and recording a podcast episode about Bill Kreutzmann's memoir as an adult, I have read far more about the Grateful Dead than I have ever listened to the Grateful Dead. I am not a huge fan of the Grateful Dead, but I am a huge fan of entertainment, and entertainment is the business of the Sphere.

As soon as the news of the building of the Sphere popped up on social media, I was intrigued. It looked hilarious when the structure was finished but hadn't yet gotten its lights. It lurked on the far edge of the Strip as a stern, round shadow, looking like the answer to the question "What if an IMAX theater was also one of Dr. Evil's lairs?" Then last summer it lit up and it felt like public opinion about it got a little hushed and reverent. This was something different, this was something special. I watched a video of Bono chattering excitedly about the Sphere, touting it as a large venue built specifically for music enjoyment first, as opposed to sports enjoyment. I watched this globular thing begin to exist at the most holy of places: the intersection between music and technology.

One signature aspect of life in the 2020s is a lot of stuff is getting consistently slightly worse, but the slightly worse stuff is getting consistently easier to acquire. Travel has become less comfortable, but you can buy a plane or train ticket on your phone; delivery apps make it possible to order expensive and terrible burritos from ghost kitchens late into the night; you can look at the whole internet on a handheld device but somehow we've decided it's okay for websites to have tons of pop-up ads again, like they did in the 1990s. Optimization has never been more optimized, and existence gets more and more frictionless with each passing year—it's never been easier to cover the basic bases of life without talking to another human being or even leaving the house.

Now, the Sphere is a bulbous addition to optimization culture. It seems to want to make your concert experience better. It wants to encrispen your audiovisuality. It wants to entertain you better than any venue has entertained you before. I wanted to know if its technological advancements would end up enacting some secret, punitive tax on humanity.

So I write to you, not as a longterm Deadhead with a firsthand grasp of the band's rich history and how it might flow within this blazing Orb Of Entertainment, but a humble music enjoyer just trying, same as it ever was, to vibe.

My husband Chris and I planned a weekend trip to Vegas not to see Dead & Co wrap up their Dead Forever residency, but to see a different type of Dead: Deadmau5. The Canadian DJ just released a new single called "Quezacotl" that tickled my brain so good it had me looking up tour dates, and lo and behold, he was in the middle of a Vegas nightclub residency. The date of his August show lined up with Dead & Co's last Sphere weekend, and we decided to make a day-of ticket purchase to their second-to-last show, in the spirit of the #PaysToWait ethos of the Under Face Value ticket price aggregation account.

We sped down I-15 on a Friday evening, playing Brett Davis's immaculate Los Angeles To Vegas road trip playlist. As a rainbow shimmered over the desert, seats dipped below $250 on a third-party app, and I pulled the trigger. 30 minutes later, we were in our room at the New York-New York casino—a handy app lets you check in with a digital key, no front desk necessary—taking quick showers, powering up with Red Bull vodkas, and putting on tie-dyed clothing, then zipping right back out the door to make the beginning of the show. The sun was setting and it was 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Our taxi driver chatted with us about the new construction in Vegas, how much he enjoyed watching the previous autumn's Formula One race, and the time when a pile of exhausted ravers commissioned him to drive them four hours from EDC Vegas back to Koreatown in L.A. He dropped us off at the large glowing ball and wished us well. A row of flower children encircled the Sphere, holding single fingers in the air. They were looking for last-minute tickets. I thought about the purported frictionlessness of our suite of digital solutions, the ease with which I secured our Sphere berth, and then I thought about the analog frictionlessness of the old way things used to be done: a handful of cash, a paper ticket, a handshake to swap 'em. It seemed absurd to have to provide these hopeful Dead fans, looking like they time-traveled from the 1970s in faded denim and swirly sundresses, with an exchange involving Venmo and the Ticketmaster app.

Every new building in America is an airport. Maybe every new building in America has always been an airport. Here is a container of people, here are the signs to point out wherever they need to go. The Sphere is a gorgeous round airport. Even after half a year of concerts, the floor was still shiny.

As we made our way to our 400-level seats, we passed innumerable Sphere employees. Some held signs that said they could help us with whatever we needed. This is where I need to say that Las Vegas is a city that contains one of the most incredible workforces in existence. It is a metropolis that relies on a vast infrastructure of labor designed to maximize your touristic enjoyment. Without the workers of Las Vegas, the entire mirage falls apart. God bless the workers of Las Vegas.

The show was just beginning when we sat down. The band were ants on a little anthill, but the Sphere screen was vast and we could take in the entire expanse of it from our vantage point. You could see the industrial seams of the structure, latticed and backlit, and the band was projected simply above the backdrop. Then the ride began.

John Mayer, the diabolical bluesman who ended up joining the post-Jerry Garcia Grateful Dead industrial complex thanks to his Pandora algorithm, served as the creative director for this bout of shows. He said in a GQ interview with Alex Pappademas that the concert was really a ride, inspired by the enclosed flight simulation of the 1980s Star Tours Disney attraction. And that's how it felt. The industrial seams turned out to be an optical illusion. They slid apart to reveal a rendering of a blue-skied Haight-Ashbury, and then we "took off" from San Francisco. I have never heard such a buoyant and perfectly tempered cheer from the crowd as we left Earth and went into orbit. The vastness of the screen turned off my sense of proprioception. My internal gravity belonged to the Sphere now.

I shall not bog this blog down with too much about the visual delights of the Dead & Co show. All I will say is that somehow, the aesthetic decisions for the big-ass screen all seemed just right. Profound silliness tempered profound elegance; gorgeous, photorealistic depictions of outer space, underwater ecosystems, and historical architecture were leavened by dancing bears and iridescent whales. At one point, the screen turned the arena into a trompe l'oeil stadium, stretching before us in accurate geometric alignment, only the other virtual attendees were thousands and thousands of dancing skeletons, and John Mayer was projected on a blimp floating above it all, making guitar faces. I couldn't help but look down at my body and think of it as a dancing skeleton too, a skeleton with the meat still on it. All 17,600 of us, just meaty skeletons, dancing. (The gummy, it did the job.)

For I was not alone in the big orb. It was full of fans of the Grateful Dead, and all its subsidiaries. And this is really what I wanted when I bought a ticket to the show: I wanted to see the people who belonged to one of the foundational modern music fandoms. Would the spirit of the Summer of Love live on in them, or were these fuckin' hippies going to exemplify the selfishness of the most wretched Boomer clichés?

All I can say, and I don't think it was just the weed gummy, and I'm sorry to be so corny, but the Dead & Co crowd really did radiate contagious positive energy, and it gave the venue an undeniable glow beyond the dazzle of all those LED lights. Everyone was smiling. Everyone was wearing some kind of softly countercultural garb. Within the sterile curvilinear environment bubbled a soup of primal goodwill. A show with such a powerful human vibe will always drag my mind toward older versions of society, drums and fire and chanting and shit. We're all very simple people at the end of the day. I took a second to pop in my handy Notes app: "thousands of people vibing in the same direction very powerful."

We introduced ourselves to our neighbors at an opportune moment. On Chris's side: two men in their 50s who followed the Dead in the '90s up until Jerry Garcia's death and were reuniting for the first time in a long time. On my side, a couple in their thirties from Canada who had been at the show the night before, only in GA, on the floor.

Now we all know that the post-2020 concert landscape has suffered greatly from lapses in etiquette, but "chompers" are a jam band pestilence that predates Covid. When I looked up the term, which I understood to have come from Phish's phandom, I noticed some definition creep; a chomper used to mean someone who "eats up" all of Phish's offerings indiscriminately, offering boorish WOOOOS or YEEEAHHS at even the mildest efforts of Anastasio et. al., but the term now just refers to people who talk a lot during a show. The New Yorker's Nick Paumgarten encountered some nasty chomper energy at his show, and I wondered if I'd do the same.

And yeah, we did have chompers. The row behind us consisted of a handful of chatty older men, and I could tell from body language alone that they were driving my Canadian seatmates crazy with their yapping. My emotional distance from the Dead granted me some anti-chomper powers (I was way more pissed, for example, at the people who chattered through Death Cab For Cutie's Kilby Block Party set) but I felt for my neighbors, and offered my solidarity.

The thing is, a lot of what those chompers were saying was shit like OH MY GOD and THIS IS NUTS and WELL HERE'S WHERE IT GETS REALLY CRAZY. And I did catch myself at points wanting to chomp as well. It was hard to stay silent when the production was so stimulating. Add chat-forward drugs and you can end up in a real conversational yearn. I'm a podcaster, after all. So I kind of understood the plight of the chompers, who needed to bear witness to the splendor of the Sphere with their mouths. And to bring it back to friction and frictionlessness—sometimes a little bad behavior from outsiders has a curative effect by giving you something structured to butt up against. It can't all be sunflowers and tie dye. We all know how the '60s ended.

What was the music like? The music was very nice. I would not say the Grateful Dead is very aligned with my core taste in music—I tend to prefer music that is much faster, higher in intensity, more condensed, and more downright artificial-sounding than the Dead's bread and butter—but piped through the Sphere's speakers, and couched within the majesty of the visuals, and flanked by a sea of people all deeply enjoying the tunes, I really liked what I heard. It didn't quite register to me as "blues" or "rock" or "Americana" or whatever. Those categorical distinctions didn't make much sense in the moment. The music sounded lush and warm, and sometimes it sounded like an element of nature, or a nice, forgotten feeling. It was uplifting, and though there was some effort in the creation of the music, the baseline affect was one of ease. It sounded like something that belonged endemically on our planet.

Dead & Company Sphere shows are broken into two sets, with an intermission between them whose time countdown appears handily on the Sphere itself, down to the minute. I appreciate gestures like this. I took the opportunity to visit the facilities. The women's bathroom, already a site of unconditional love at the most neutral establishments, was ablaze with affection. Women were hugging, women were telling one another about their jewelry-making practices. The rubber wedge holding the door open slipped out and I jammed it back in before the door flew shut, then made eye contact with a woman in her early twenties standing behind me. "Whew, that was a close one," I said. "The future is female," she responded. We started cracking up.

By the time the second set rolled around, I had gotten used to the environment enough to stand up and do some decorous wiggling. It was a perfectly calibrated entertainment: I'd tune my ears into the music, then if the music lagged a little, I'd get lost in my own thoughts for a while, and when I got bored with my own thoughts, I'd see something else insane on the screen and focus on that. In this way, my attention was triangulated, somehow present and blissfully zoned out at the same time. Dear god...my attention was optimized.

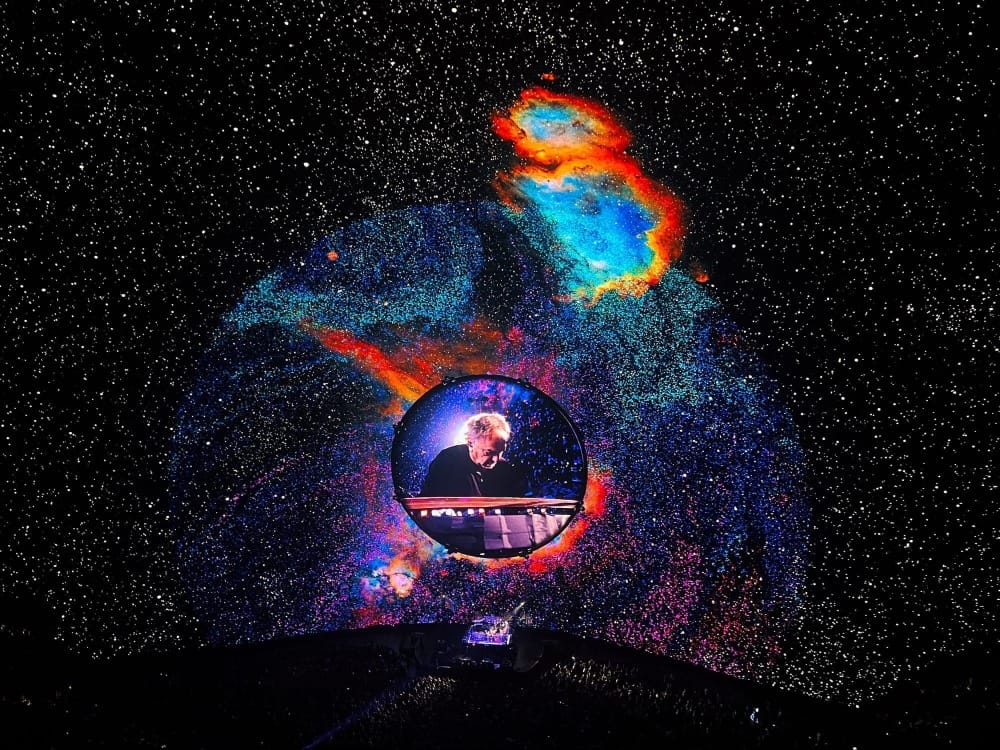

My favorite musical moment happened at the end of the "Drums" and "Space" segment, a historical Dead jam whose percussion, at the Sphere, triggered vibrations in the venue's haptic seats. In the GQ interview, Mickey Hart described the low-frequency tones he generates during this segment as "that place before sound turns into feeling...coming right up your perineum...filling you with that kind of energy—the serpent power, we would call it in yoga." That is a lovely way of putting it; I would describe it as "the power of God was in my butthole." After all that noodling and pounding, everything slowed down. The stimulation of the prior drum solo collapsed into a regular rhythm. Hart appeared in a circle in the cosmos on the screen, and it felt in that moment that he was bringing everyone into the same pulse, regulating thousands of people on various calibers of trip into one universal meditation. It was beautiful.

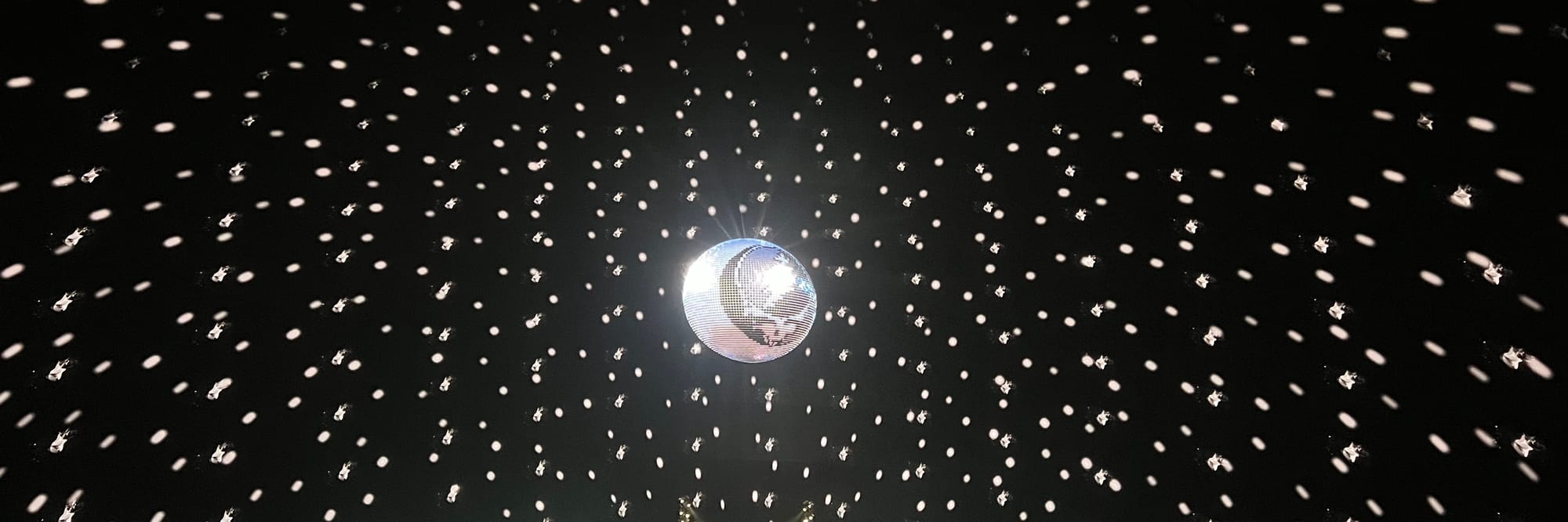

If you spend a lot of time on the internet, as I do, everything can seem very flat. You have a flat screen, and you look at flat social feeds. My blog even looks kind of flat. Is it stupid to get excited about being in a space that is so actively round? That's what I couldn't get over. It wasn't just the screen that gave the impression of roundness. Even the way the crowd cheered felt circular somehow, like it was feeding back into itself. Was that the design of the space, or the energy of the band and the people? I thought about singing rounds, how different people committing to their individual parts creates something bigger and more interesting. I thought about Donald Trump's glowing Saudi orb. I couldn't help it! There is power in a round thing.

We left a little early, I will admit. Our friends Jake and Betsy were meeting us for the weekend and we realized our experiential cups were as full as they could be. I have a personal theory of socialization called Leave On A High Note (LOAHN)—don't wait around for things to start sucking if you're ready to dip. A line of Sphere employees waved us out, wishing us a good night. We took another taxi to the Peppermill, my favorite restaurant in Las Vegas. It's full of lush greenery and slices of neon purple and pink lighting, and the salads they serve are unparalleled. I ordered a Cosmo. We let ourselves chomp at last. The Cobb was delicious.

Oh, Vegas. I love being a tourist in this city. I love that everyone is here to be entertained. I love watching packs of you-know-I-had-to-do-it-to-em men and big groups of women in coordinated satin outfits roam the casinos. I love loud music and bright lights. I love being fooled, I love being dazzled. Maybe it's the Catholic upbringing in me, beauty and terror delivered via stained glass, cranked to maximum wattage.

Sometimes I wonder if I am addicted to entertainment, that my desire for it comes from a darker place than I can admit. I wonder if my desire to wear a miniskirt and drink spiked energy drinks and dance to Taio Cruz is trying to quiet something insistent in my brain, drown it out with Too Much Fun. After all, one of my consistent bits is that I say that I would have enjoyed every second of the cruise David Foster Wallace experienced so much existential dread upon—I would have taken all its pleasure straight to the dome and, as Robert De Niro says at the end of Casino, that's that.

But I keep thinking of that mass meditation during "Space." The cost of admission to it was certainly steep. I spent money to walk in the door, and allowed myself and my belongings to be searched by security in order to find my seat. I was in a building that cost several billion dollars to construct. It was pristine and massive with perfect acoustics and vast personnel at the ready, and I was undeniably a customer. But "Space" was more than commerce, and more than entertainment, and I think everyone in there knew it. It was sublime. It was made of people, it would have been nothing without people. People aren't money, people are messy, people are all there is.

A post-script: the next night was Deadmau5, at a nightclub called Zouk, which is inside one of the newest business concerns in Vegas, Resorts World (another beautiful airport). The show was definitely lit, and the sound and lighting were wild, but the layout inside the club was almost painfully stratified, with random pockets of places you simply weren't allowed to go if you didn't have a lot of money. The energy in there was not very round at all. Not spherical in the slightest.

Of course, I saw a guy wearing Grateful Dead merch, and we did a quick mutual gush about what we'd seen the previous night. This is what happens when you catch one of their shows, I guess. You have people, and they're not hard to spot.

We listened to Cornell 5/8/77 on the ride home. And yesterday I queued up an old episode of Time Crisis that had some Grateful Dead commentary in it, and a playlist that Jake Longstreth put together as a beginner's guide to the Dead. And all I have to say now is: uh oh!!!

If you read 3500+ words on my exSpherience...wow thanks. Thanks for reading the blog, and if you like it, tell a friend, start trading URLs on Shakedown Street.